|

"Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.” - Oscar Wilde This post is for the The Silent Cinema Blogathon hosted by In The Good Old Days of Classic Hollywood. October is my favorite month of the year. Not just for the changing foliage, pumpkin lattes, pumpkin muffins, pumpkin beer, pumpkin bread, and pumpkin pie. But also for the last day of the month, Halloween. I don’t know why, but I have always loved this holiday. As a child my family did not celebrate Halloween. No passing out of candy, no going around to stranger’s houses, and certainly no scary movies. Yet I was always drawn to it, the atmosphere of it. Maybe the biggest aspect of this holiday, if not for scaring people, is dressing up. What are you going to be for Halloween? is the question starts to pop up around the beginning of the month. I don’t typically dress up for Halloween, but I have friends that do it every year, even if they’re the only person dressed up. The basic premise is that you can be anything you want on Halloween. It's the one night of the year where is it not frowned upon to dress up like a vampire hooker, or a disco zombie. This raises a question, why do we love to be someone we are not? I think this relates, fittingly, to our fear. Our fear of who we are. Our identity. Being someone you’re not has its benefits. We all act unlike ourselves at different points in our lives, whether it’s to impress your girlfriend’s father, or to get into a club underage. But in the end you can’t escape who you are. Being your true self is one of the biggest fears we will face as humans. And it doesn’t matter how you dress yourself up, eventually your true nature will be revealed. This brings me to the film I would like to talk about, The Unholy Three of 1925. Not to be confused the its later remake, made in 1930, starring two of the same main actors Lon Chaney and Harry Earles. The Unholy Three (1925) is the story of three, obviously, sideshow performers who become burglars. Directed by Tod Browning, The Unholy Three marks the beginning of a series of films made with the dynamic duo of Browning and Chaney. A pairing that would lead to such great silent era films as The Unknown (1927), The Blackbird (1926), and West of Zanzibar (1926). The film opens at a side show. A backdrop Browning would visit later in his masterpiece Freaks (1932). The sideshow boss is leading the crowd around introducing them to each performer with copious amounts of alliteration, after which they perform. This introduction not only gives us a backdrop for each individual character, but also gives us a glimpse into the nature of each character. Their perceived identity and their actual one, which is a theme that will carry forward as the film progresses. Professor Echo, the ventriloquist and his figure Nemo perform an act then attempt to sell some joke booklets. The very nature of Echo’s act is about deception. The skill of putting a voice into an inanimate object is one that will be very useful later in the film. But we also get a glimpse into the other side business Echo has as skill performer, charming women. While he performs, his girlfriend Rosie picks the pockets of the customers. When they meet up after the performance there is a sense that Echo is merely in the relationship for financial gain. He likes control, which can lead to jealousy. A flaw that will cause trouble later. Hercules the strong man is introduced bending a horseshoe. He does his act and sells something to a boy This scene also has one of the best visual gags in the film. A young boy, who idolizes Hercules, is told that if he doesn’t smoke he will grow up big and strong like Hercules. Who in turn lights a cigarette, unbenounced to them as the mother and son walk away. It makes me laugh every time I watch it. Tweedledee, the little person is introduced as “Twenty inches - Twenty years - Twenty pounds - The twentieth century curiosity!” After some berating by some women and a young boy. Tweedledee begins to get angry. Eventually kicking the little boy in the face, which brings on a riot involving Hercules among others. With the side show shut down the three men must come up with another way to make money. They name themselves the Unholy Three. Fast forward to sometime in the near future. The three men set up a bird shop selling parrots that don’t talk, at least not for anyone except “Granny” O’Grady. Using customer information from the store, the men gain access rich people’s homes. No one would suspect an old lady and a small child to be casing a home. But when a burglary goes bad and a man is murdered things start to go south for the group. Luckily for them, they have the perfect scapegoat, Hector. Hector works for Mrs. O’Grady, Echo in disguise, as a clerk in the bird shop. He helps keep the shop in working order. In addition to this, he makes deliveries for the shop. He is also in love with Rosie. Little does he know that Granny O’Grady is unwilling to share Rosie. Echo’s jealousy will inevitably lead to the collapse of the unholy three, the trial of Hector, and some unfortunate incidences with an ape. After Hector taken away by the police for murder, the unholy three, Rosie, and Echo’s pet ape retreat to a cabin outside of the city. There Rosie pleads with Echo to help get Hector released, telling him that she will stay if he does this for her. So Echo goes to the trial. Meanwhile, Hercules just happens to also be into Rosie. He tries to get her to leave with him, and the loot of course. Tweedledee doesn’t like this one bit. He releases the ape in an attempt to kill Hercules. The ape gets Hercules, but not before he kills Tweedledee. Back at the trial Echo comes forward with the truth after some distressful decision making in the courtroom. Both he and Hector are set free. Echo returns to the sideshow, telling Rosie to be with Hector. Each of the three men construct multiple identities to deceive others of their true nature. Echo’ complex identity is built around thought and planning. He is the brains of the unholy three. His act is predicated on control. This control spreads into his interaction with others. When speaking to Rosie he is more manipulative than loving. We get the sense that maybe he doesn’t actually love her, he just wants to control her. This control makes Echo very jealous and leads to animosity within the group of men. His attempt to control Rosie by forbidding her from spending time with Hector only leads her to do it more. This jealously also won’t let him leave the two of them alone, which leads to the other men venturing out on their own. Echo does not reveal his true self until he is forced, by confessing in the courtroom. Showing his true love for Rosie by freeing Hector. He is the only member of the unholy three who seems to have a conscience and is not driven by greed entirely. Just as he tells the crowd “That’s all there is in life, friends - a little laughter - a little tear.” Echo is the only person who escapes the consequences of their unholy actions. By having a change of heart and revealing to the world his true nature he is redeemed. Both Hercules and Tweedledee’s identities are tied to their own physical attributes. While one attempts to make up for his size, the other confronts any attempt to belittle his strength. A very similar theme Browning would also employ in Freaks (1932). Hercules is introduced to the audience at the sideshow as “The mighty... marvelous... mastodonic model of muscular masculinity!” This phrase epitomizes Hercules’ entire identity. He is the only character of the three who character in the bird shop is not drastically different than his sideshow persona. He is simply the son-in-law. His job is to be the muscle, the heavy. Hercules’ identity is in his strength. When Tweedledee threatens this strength by calling him a coward, he reacts by leaving Echo behind. This action leads to the death of the homeowner, which later causes downfall of the unholy three. Hercules even attempts to take Rosie away from Echo. Tweedledee or Little Willie has a complex about his size. While his diminutive stature is directly related to his job, it is also a part of his identity. He doesn’t want to identified as little, or inferior, or a child. Ironically, he plays a small child when the group moves into the bird shop. He defends his size with violence or the threat of violence, not afraid to kick a small child in the face or threaten violence to Rosie if she talks stating “If you tip the bulls off to who we are, I'll lay some lilies under your chin.” Which is probably the greatest line to ever come from a small man dressed up as baby in film history. The animosity felt by Tweedledee about his size also makes him aggressive verbally. He taunts Hercules, manipulating him to get the results he wants. This behavior ultimately leads to his death. Because let’s face it, a twenty inch tall man can only push people around for so long before they push back. The Unholy Three (1925) is a story of identity, deception and redemption. It is a story of both perceived and true identity. A story of how people can use perceived identity to deceive others, but in the end true identity will always show through. Through this, it shows us the consequences of deception. And lastly it shows us why you should never have an ape as a pet, even if it is actually just a small chimp and some forced perspective. It will mess you up.

2 Comments

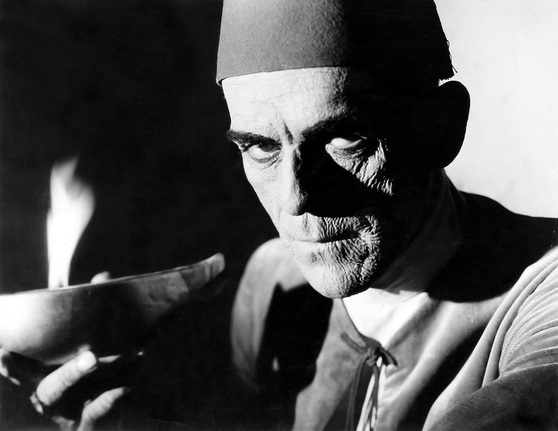

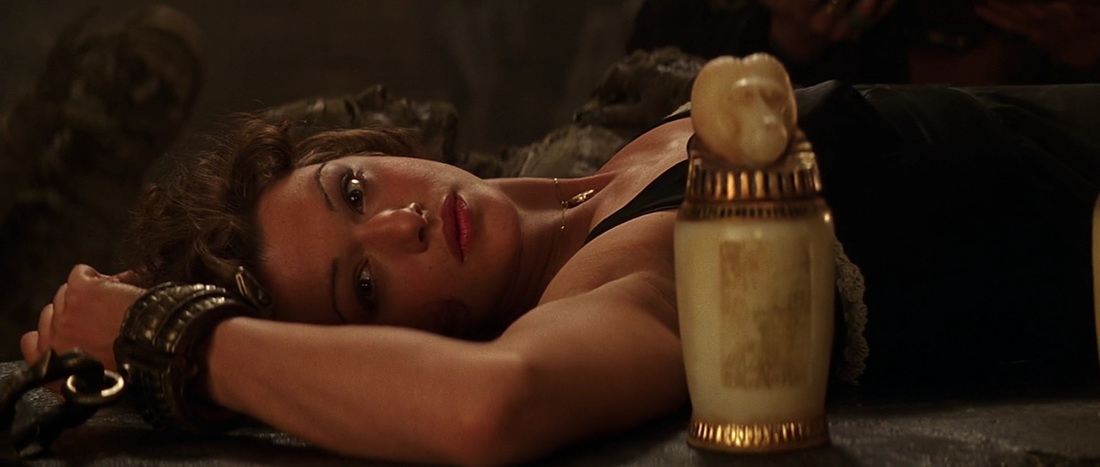

"That which has been is that which will be, And that which has been done is that which will be done. So there is nothing new under the sun." -Ecclesiastes 1:9 This post is for the They Remade What? Blogathon hosted by Phyllis Loves Classic Movies. Photocopy machines puzzle me. How can this machine use light to make an exact copy of my document so quickly? And how is it that the same machine can possibly get jammed 14 times in one day? This makes me think about the photocopies themselves. If you make a photocopy of a copy, then a copy of that copy, etc. etc. and so on and so forth. Eventually whatever you’re copying will begin to fade. Because a copy is just that, a copy. It is not the original. While it may have traits of the original, it will never be the original. Innovation is driven by copying ideas and improving them. It’s what led the Egyptians to build pyramids and cars to have more horsepower. On the other hand, art doesn’t exactly work the same way. Creativity isn’t cultivated by imitation. It’s often frowned upon. Which brings me to the topic at hand, film remakes. Let me first say that while I understand that remakes have been occurring since film began and even before this in literature, the recent rash of remakes in the last decade makes it seem as though we are running out of ideas . But has there really been anything new in a long time? In his book, 36 Dramatic Situations, Georges Polti designates that all stories or performances in human history can be boiled down to only 36 situations. Whether this is true or not can be argued, however, it does simplify matters and point out that perhaps we are all looking for the same ideals or concepts no matter what the plot of the story or who wrote it. If this is true, it is inevitable we would retell stories from the past. Even Polti himself states he is continuing the work of Carlo Gozzi, who created a list of 36 tragic situations, therefore expanding upon something that already exists. Now I know that this post is for a blogathon titled They Remade What? And this should be an attack on all things remake. Let’s get one thing straight. For the most part, I dislike remakes. Especially now, when we are remaking films from my childhood. You can call it a reimagining, or a retelling. It won’t change what you are doing, copying. That being said, the films I wanted to look at are The Mummy (1932) and The Mummy (1999). I think that this represents a good way to remake a film. The original Mummy (1932) starring Boris Karloff was part of Universal Pictures monster series which began with Dracula in 1931. With the popularity of the next film, Frankenstein, Universal realized that they had something. What makes The Mummy interesting is it contains two elements from those previous films, a similar structure to Dracula,and Frankenstein’s star, Boris Karloff. With the popularity of Egypt in full swing after the discovery of King Tut’s tomb in 1926, Universal took full advantage of the popularity of all things Egypt. It paid off. Although there was no such find in 1999, Universal decided it was time to remake a film they had made some 60 years earlier. This time giving the plot and theme a little more action adventure rather than horror. In reality, The Mummy (1932) isn’t horror film either. While containing horrific elements, it is a love story. It’s your typical boy meets girl, boy is buried alive, girl dies, boy is resurrected and tries to resurrect dead girl story. We’ve seen it so many times before. But whereas Imhotep in the original is a rather sympathetic character, in the remake he is simply a creature of unspeakable power. Both films draw some of their sympathy from this idea that perhaps the Imhotep is the victim of circumstance. He can’t help that he has some gifts, like the ability to kill people either through sucking them dry or choking them telepathically. Are we to blame him for using his knowledge of Egyptian magical practices to bring back his true love, wouldn’t you do the same? This shift in the construction of Imhotep’s character from the first film to the remake is directly related to the thematic elements of the two films. The original film’s Imhotep if more menacing. He walks with rigidity. His movement and speak are slow, as if he is still coming out of his mummified state. His power over others if primarily mental. Once it has been discovered that he, Ardeth Bay, is actually Imhotep it is not as if he can immediately be destroyed, for he possesses unseen powers. The remake constructs the character of Imhotep as someone or something with overt unspeakable power. He can mesmerize people, move sand, vomit locusts Exorcist style, and of course, suck people dry. This type of character correlates well to the type of action in the film. This Imhotep is fast, getting immediately to the point as soon as he is resurrected. One of the key differences in the remake and the original characterization of Imhotep how they are resurrected and later introduced to the other characters. Both are brought back to life through the reading of a scroll, but the original Imhotep escapes only to appear ten years later. The curse that was read on the box did not have immediate consequences. Whereas with the Imhotep from the remake, the audience gets to participate in his restoration. Perhaps that is what he was doing for those ten years, sucking a bunch of people dry and stealing their eyeballs. Taking the audience along for the restoration in the remake creates an Imhotep that we as the viewer can not relate to as much. He is truly a monster and we bare witness to this truth. An interesting change from the original to the remake is the character of Ardeth Bay. In the original film he is the alter ego of Imhotep. In the remake he is a completely different character, the protector of the creature’s final resting place and aides in destroying him. The only element other than the name that remains constant in both films is their knowledge. Both characters possess a knowledge of past, one first hand and the other passed down through generations. Part of this is because of the construction of the character Imhotep. He doesn’t need an alter ego when he’s running around in the dark ripping eyes and tongues out. Whether the use of this name in the remake is simply an homage to the original, or something more, is unknown. The women in both films are looking for something. While Helen is looking for something outside the world she is embedded in, longing for a connection to something greater, Evelyn is searching for recognition in a field that is dominated by men. Helen is transformed by Imhotep’s words because she is connected to a past life she doesn’t remember. Evelyn’s transformation comes through her own initiative and through the actions of other major characters, primarily Rick. Both The Mummy (1932) and The Mummy (1999) tell the story of love lost and an attempt to find it once more. The way in which they tell this story varies. While I hate to admit this, the 1999 remake of The Mummy is a good stand alone film. I am not saying that I agree with the remaking of classic films. But, I think that we have to come to an understanding that we as humans tend to repeat ourselves. And that one story can be told in multiple ways. One man's Cupid and Psyche is another man's Romeo and Juliet, Under Pressure to Ice Ice Baby, or Ghostbusters to Ghostbusters. No, that last one doesn't make sense, but anyway, let's not knock all remakes. Just most of them.

|

The Distracted BloggerI watch movies. I write about them here. I watch more movies. I get nothing else done. Archives

April 2020

Suggested Reading...Sunset Gun

Sergio Leone And The Infield Fly Rule Self-Styled Siren Wright On Film Video WatchBlog Coffee Coffee and More Coffee The Nitrate Diva She Blogged By Night Acidemic These Violent Delights Movies Silently Classic Film and TV Cafe Speakeasy Shadows And Satin MovieMovieBlogBlog Girls Do Film CineMavin's: Essays from the Couch Sliver Screenings A Shroud of Thoughts Stardust In The Good Old Days of Classic Hollywood Silver Scene Criterion Blues Now Voyaging Serendipitous Anachronisms Outspoken and Freckled B Noir Detour Journeys in Darkness and Light Easy Listening...Criterion Close-Up

Criterion Cast The Talk Film Society Wrong Reel Flixwise Daughters of Darkness The Projection Booth BlogathonsBlogathons I've done. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed