|

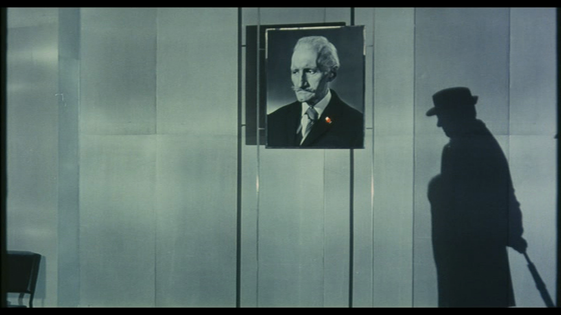

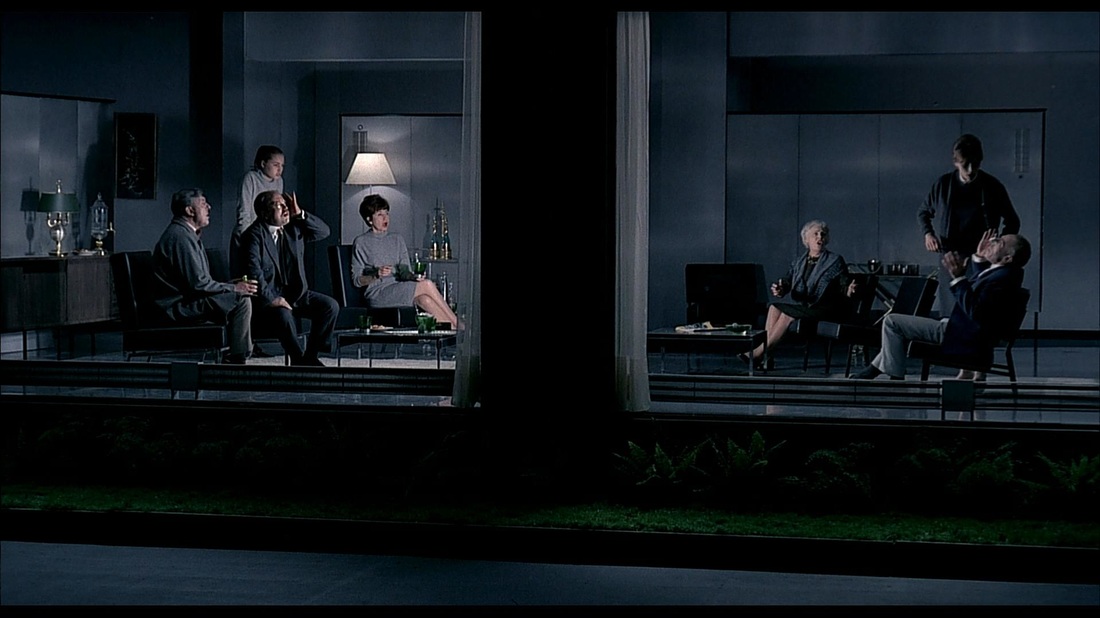

“Comedy is the summit of logic.” Jacques Tati This post is part of the See You In The Fall Blogathon hosted by MovieMovieBlogBlog. Physical comedy in film is a funny thing. Yes, I did just write that sentence. Please keep reading. What I am trying to say is that physical comedy works like no other form of comedy. It is easily accessible, giving it the ability to cross language barriers and age differences. This is because physical comedy is visual. No one is telling a joke, and there are no one liners. There are, in a sense, no explicit cultural standards that have be understood in order to appreciate it. This is why it works so well in film, a visual medium. At the same time it can contain depth. It can tell us more than what it showing us on the surface of the gag. Whether that is philosophical or ideological, it can be grounded in some deeper meaning. Physical comedy characterized by the visual gag. The gag is the comic effect or joke being conveyed. In some cases the gag can span the whole film. While seemly simply in its design, the physical comedy gag is intricate in its set up. It is this intricacy and regard for detail that made me think of Jacques Tati as a subject for a post on physical comedy. The films of Jacques Tati are not overtly slapstick. His comedy is more subvert, but still within the vein of physical comedy. I chose PlayTime (1967), because it is his tour de force, the work that took him years to complete, was a financial failure, and is considered a masterpiece today. PlayTime is one of four films featuring the character of Monsieur Hulot, played by Tati himself. Much has been sad about this film, its use of space, sound, set design, mise-en-scene, color, and movement. What I would like to focus on are just two scenes in the film that really show Tati’s ability to use subtle physical comedy. Particularly the use of sound and space. PlayTime is a critique of modernity, its built environments, and how people are effects by those environments. Therefore it uses those built environments to visually tell the audience something. It is interesting to note that Tati always shot his films without sound. Inserting the soundtrack in afterwards in post production. PlayTime is very effective visually. But it is the addition of sound heightens this effect dramatically. PlayTime takes sound design to a whole other level, integrating it into every visual aspect of the film. Monsieur Hulot meet Monsieur Giffard, in a minute. After we are introduced to a group of American tourists, a very important old man, and a faux Monsieur Hulot, we finally meet the real M. Hulot stepping awkwardly off a bus. We already get the sense that he is out of place. This awkwardness relating to the trappings of the modern world is nothing new to M. Hulot. As this is demonstrated in the previous Hulot film, Mon Oncle (1958). He makes his way to an office building where he shows the porter a slip of paper. After some finagling with a large switchboard, the porter arranges for M. Giffard to meet M. Hulot. Using forced perspective, we see M. Giffard approaching. Hulot does not. The clip clap of Giffard's shoes on the floor tell us he is near, Hulot stands and is told to sit back down by the porter, who in turn sneaks another drag from his cigar. There is a complete disassociation between what we are hearing and what we are seeing. Hulot doesn't know what the audience knows in regard to Giffard's distance from him because the sound of his shoes are telling him that M. Geffard is close. It takes a long time for Giffard to reach Hulot. This reminds me of a scene in Monty Python's Holy Grail (1975) where Lancelot is storming the castle after his horse is shot by an arrow. The guards see him come up over the rise repeatedly. The shot is played over ad nauseum until, bam! He's at the gate. I get the sense that Tati is attempting to give the audience the same type of feeling. How could Geffard possibly be that far away? And perhaps something deeper is being said here, that modern buildings misuse space. M. Giffard is a busy man, as the film progresses we see how busy. So he has M. Hulot wait in a sparse, glass waiting area. It is here that Hulot encounters a reoccurring set piece, the black chair. The chairs in the waiting area have the ability to bounce back after being sat in, or pushed down. Something Hulot finds very curious, and later learns is a selling point for the chair. As he moves around the waiting area initially, the sound we hear is the outside noises of the street. Almost as if Hulot is a museum exhibit. An exhibit that no one looks at. As we move inside with Hulot the sound of the interior is static, humming. Tati desired it to sound as if it was a vault. The chairs make a funny, fart like, noise when they retake their form. Hulot finally finds a spot to sit. M. Lacs is escorted into the room and sits on the opposite side of the door from Hulot. M. Lacs is robotic in his movements, each of which have a sound effect. These sounds in turn make his almost ritualistic movements comical, giving them rhythm. We, along with Hulot, can only stare at M. Lacs. M. Lacs brings a one man band of sounds into this sterile soundless environment. His movements are exaggerated by the soundtrack placed on them. He is a product of the modern work space. Making sure his pants are clean, his nose is properly moisturized, and his papers are in order. Like that of M. Geffard, M. Lacs actions are exaggerated for comedic effect. The introduction of this character to the waiting area only further indicates Hulot's unfamiliarity with modernity. This misplaced feeling is apparent in the next scene I would like to discuss. The farting chair and M. Geffard reoccur in it as well, tying the two scenes together both plot and thematic elements. Once Hulot finally leaves the building, unable to find M. Geffard, he gets back on a bus. Getting off there is someone yelling his name. It is an old friend from the war, who invites Hulot into his apartment for a drink. However the camera doesn't go with Hulot, but stays outside of the apartment. Sounds heard are that of the street outside. Much like that of the earlier scene when Hulot first enters the waiting room. The wide angle shots during this scene give us a view of the entire apartment, which has a floor to ceiling window much like that of a store front. As the camera pans both adjacent apartments come into view. They are mirror images of each other, sharing a common walls, which houses a television. This camera movement gives the viewer the ability to see what is going on in both apartments simultaneously. Tati uses this effect to bring some visual comedy into play. What Hulot doesn't know is that Geffard is actually in the apartment adjacent to the one he is in. He is shown all the amenities of the apartment, the lamp with the cigarette holder hidden inside, those farting chairs, and the television. The comedy comes from the way in which Tati lets the viewer create the story. As Hulot is inside, the camera never goes inside, so we never hear a word they are saying. We are forced to make up in our minds what is happening. Meanwhile, Tati letting us in on joke as if the camera is showing something funny to the audience it noticed while being forced to wait outside for Hulot. One of the best uses of the camera to do this is after Hulot has left, and Geffard has been forced to take the family dog for a walk, each apartment is left with only one person in it. Hulot's firend, who is watching television while changing. And Geffard's wife, who is also watching television. As the camera pans to the middle of the two apartments the dividing wall between the them visually becomes less apparent. Thereby making it seem as though the woman is watching the man strip. Brilliantly funny use of a simple camera move. Tati is also continuing the theme of transparency that began in the office building. That the modern world offers no privacy. And therefore we in turn lose a bit of self with this loss. Of course he does this through a visual satire of the modern world. While PlayTime is does not have a slapstick of a Stooges skit, it does have elements of a great physical comedy. Timing, well thought out visual gags, and depth. Because sometimes a pie in the face is more than just a pie in the face. Or as Napoleon put it "Un bon croquis vaut mieux qu'un long discours" (A good sketch is better than a long speech).

If you have not seen this film, I encourage you to check it out. It contains so much more than the two scenes I talked about in this post. Also, take a look at other films by Tati. You won't be disappointed. Want to know more about the genius of PlayTime? Check out this video essay by David Cairns done for Criterion https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/3351-playtime-anatomy-of-a-gag

6 Comments

9/24/2015 05:42:49 am

Lovely review of a Jacques Tati classic. Thanks so much for contributing to the blogathon!

Reply

9/24/2015 02:08:11 pm

This looks marvelous. Can't believe I haven't seen it! I'll be watching for it.

Reply

9/25/2015 07:21:45 am

Yes, I would say it's a must see. That along with the other Hulot films prior to it. Thank you for reading and commenting.

Reply

Jean Charles

3/8/2023 06:48:23 pm

Hi,

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

The Distracted BloggerI watch movies. I write about them here. I watch more movies. I get nothing else done. Archives

April 2020

Suggested Reading...Sunset Gun

Sergio Leone And The Infield Fly Rule Self-Styled Siren Wright On Film Video WatchBlog Coffee Coffee and More Coffee The Nitrate Diva She Blogged By Night Acidemic These Violent Delights Movies Silently Classic Film and TV Cafe Speakeasy Shadows And Satin MovieMovieBlogBlog Girls Do Film CineMavin's: Essays from the Couch Sliver Screenings A Shroud of Thoughts Stardust In The Good Old Days of Classic Hollywood Silver Scene Criterion Blues Now Voyaging Serendipitous Anachronisms Outspoken and Freckled B Noir Detour Journeys in Darkness and Light Easy Listening...Criterion Close-Up

Criterion Cast The Talk Film Society Wrong Reel Flixwise Daughters of Darkness The Projection Booth BlogathonsBlogathons I've done. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed